An Ode to Merge Join

Merge join is such a delightful algorithm.

I’ve written a lot of Python that syncs data sources (CSV dumps, API responses, etc.) with a relational database. No matter your approach, you will need to figure out what’s been added, what’s changed, and what’s been deleted, then handle those cases appropriately.

My early attempts would read the source data into a hash table and then compare it with my database. It works, and it’s fast. But at ten million rows the hash table alone can consume 3 GB of RAM. That’s not 3 GB of data; it’s Python object overhead wrapping maybe 300 MB of payload. RAM prices being what they are, this is a budget problem as much as a technical one.

A merge join does the same comparison in 19 MB. Constant regardless of dataset size. In 25 lines of Python.

The algorithm

Two sorted inputs, two pointers. Advance whichever pointer has the smaller key. When the keys match, you have a pair. When they don’t, you have an insert or a delete.

def merge_join(left, right, left_key, right_key):

left_item = next(left, None)

right_item = next(right, None)

while left_item is not None and right_item is not None:

lk = left_key(left_item)

rk = right_key(right_item)

if lk < rk:

yield (left_item, None)

left_item = next(left, None)

elif lk > rk:

yield (None, right_item)

right_item = next(right, None)

else:

yield (left_item, right_item)

left_item = next(left, None)

right_item = next(right, None)

while left_item is not None:

yield (left_item, None)

left_item = next(left, None)

while right_item is not None:

yield (None, right_item)

right_item = next(right, None)

It takes any two sorted iterables and key functions. The output encodes the operation through presence and absence: (left, None) is an insert - the row exists in the source but not the destination. (None, right) is a delete. (left, right) is a potential update - both rows are right there for field-by-field comparison. A full outer join on unique keys in a single pass.

Ondrej Kokes blogged about a Python implementation that cleverly uses heapq.merge() and itertools.groupby(), but it is slightly slower in my tests and didn’t save that many lines over the hand-written version above.

Using it for sync

This is why I love this approach. Stream both sides row by row, sorted by the same key, and the sync logic practically writes itself - generators for your source and destination, and the sync function is left with a single loop that has clear insert/modify/delete conditions:

def csv_row_generator(csv_path):

with open(csv_path) as f:

next(f) # skip header

for line in f:

parts = line.rstrip("\n").split(",", 3)

yield (int(parts[0]), parts[1], parts[2], float(parts[3]))

def db_row_generator(conn):

cursor = conn.execute(

"SELECT id, name, email, amount FROM records ORDER BY id"

)

yield from cursor

def sync(conn, csv_path):

csv_stream = csv_row_generator(csv_path)

db_stream = db_row_generator(conn)

updated = deleted = inserted = 0

for csv_row, db_row in merge_join(

csv_stream, db_stream,

left_key=lambda row: row[0],

right_key=lambda row: row[0],

):

if db_row is None:

# new record handling goes here

inserted += 1

elif csv_row is None:

# deleted record handling goes here

deleted += 1

else:

if csv_row[1:] != db_row[1:]:

# updated record handling goes here

updated += 1

return updated, deleted, inserted

At no point does either the full CSV or the full query result live in memory. One row from each side, compared, yielded, discarded. Memory usage is constant regardless of dataset size.

Interactive example

Step through the algorithm on a small dataset — an 8-row CSV synced against a 7-row database table:

Why this works

The merge join’s power comes from leveraging existing order. Source data almost always has a natural order - sequential IDs, timestamps, alphabetical keys. On the destination side, an index on the join key makes ORDER BY essentially free: the database walks the index in order rather than sorting at query time. You get O(n) time and O(1) memory without paying the O(n log n) sort cost.

This precondition is also the pattern’s main limitation. If your source data has no natural order and you need to sort it first, you pay O(n log n) time and potentially O(n) memory - and a hash join or a temporary table may be the better choice. But in practice, most data has a natural key.

What the alternatives cost

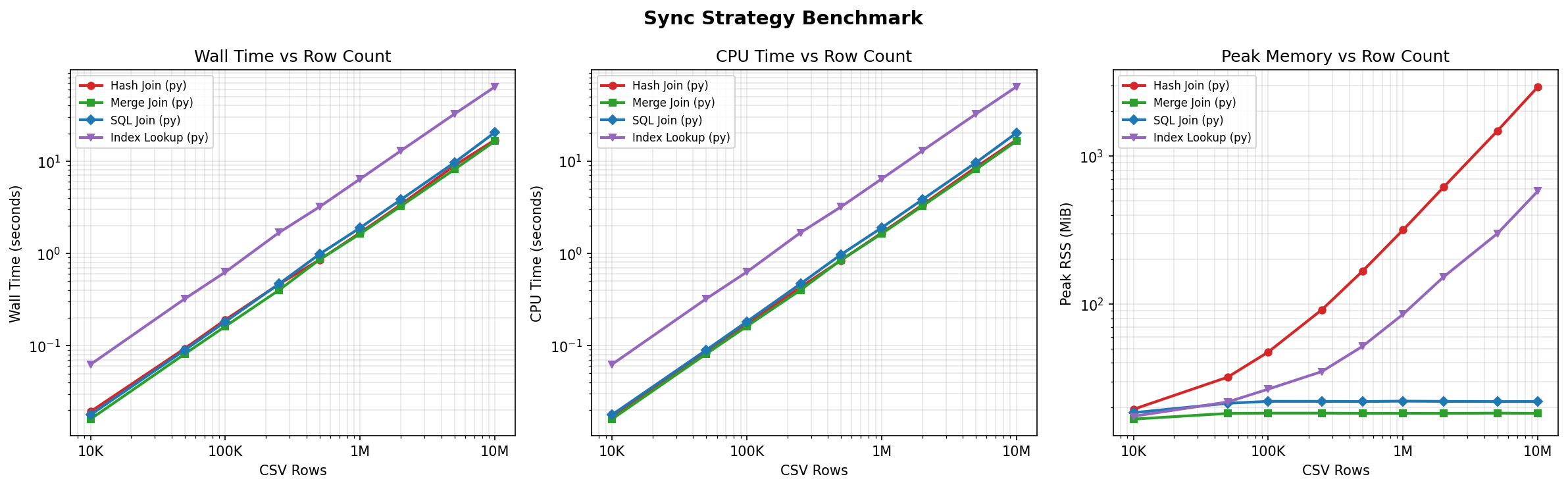

I benchmarked three other approaches to the same CSV-to-database sync:

Hash join - Load the entire CSV into a dict keyed by ID, scan the database, probe with dict.pop(). The most natural approach. Same speed as merge join, but at 10 million rows, the dict consumes 3 GB of memory - 160x more.

SQL join - Load the CSV into a temp table and diff with SQL JOINs. Competitive on memory (23 MB), but 17% slower. A reasonable choice when you want to keep everything in SQL.

Index lookup - SELECT ... WHERE id = ? for each CSV row. Appears memory-efficient - one row at a time - but still requires a set of all CSV IDs for delete detection. At 10 million rows, that set uses 609 MB. The per-row queries make it 4x slower.

Benchmarks

I benchmarked all four strategies across dataset sizes from 10,000 to 10,000,000 rows, using SQLite and measuring wall time and peak resident memory with /usr/bin/time -v.

Merge join and hash join are essentially identical on wall time (~16.5s at 10M rows). The merge join gives you the memory win for free - there is no speed tradeoff.

The rightmost panel is the real story. Merge join memory is flat - 19 MB from ten thousand rows to ten million. Hash join memory is linear, reaching 3 GB at 10M rows. That’s a 160x difference. For a production sync job, this is the difference between “runs anywhere” and “needs a beefy server.”

Watch out for driver buffering

The benchmarks use SQLite, where cursors are naturally streaming - the library walks the B-tree in-process, so iterating the cursor truly reads one row at a time.

Most client-server database drivers do not work this way by default. psycopg2, for example, fetches the entire result set into client memory on execute(), even if you iterate the cursor row by row. This silently breaks the O(1) memory property and gives you the same ~3 GB footprint as hash join.

To preserve streaming behavior, you either need to do your own batched reads or use server-side cursors - a per-cursor option that tells the driver to fetch rows in batches rather than all at once. The merge join code itself doesn’t change. Easy to get wrong if you don’t know about it, but easy to fix once you do.

Benchmark caveats

All benchmarks use SQLite (in-process). With PostgreSQL or MySQL, the index lookup strategy would be catastrophically worse due to network round trips per row.

A bit of history

The underlying idea, walking two sorted sequences in lockstep, is one of the oldest in computing. John von Neumann wrote a merge routine for the EDVAC in 1945, likely the first program ever designed for a stored-program computer. (Knuth tracked down the original manuscript and analyzed it in 1970.) Thirty years later, Blasgen and Eswaran formalized the sort-merge join for IBM’s System R, the prototype relational database that gave us SQL. Every major database engine still uses it.

Merge joins in the wild

Git uses a merge join to compute the diff between two or more tree objects by iterating through their alphabetically sorted paths in lockstep, which allows it to identify additions, deletions, and modifications.

GNU Coreutils includes a join tool that does a merge join on two text files.

The PostgreSQL merge join is wrapped in some kind of state machine to handle the fact that it has to pause/resume constantly and handle duplicates without unlimited memory buffering. In other words, if I squint at it, I can pretend like I understand what it’s doing.

Summary

Given two sorted streams, the merge join produces a complete diff in a single pass: 19 MB of memory where hash join uses 3 GB, at the same speed, in 25 lines of Python. It generalizes to any pair of sorted iterables - CSV-to-database, API-to-database, file-to-file.

The code is at github.com/ender672/application-level-merge-join.